Trident Missile

India has the batting armoury

to pulverise any bowling attack in the coming decade

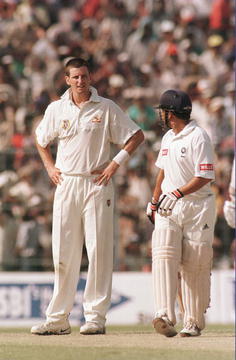

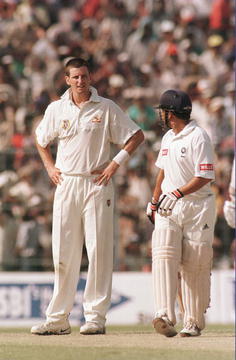

THE DESTROYER: In Chennai, when the

Australians managed to squeeze a tiny first innings lead, Sachin

Tendulkar walked up to coach Anshuman Gaekwad and said India

could have a sniff at victory if somebody scored a quickfire 80.

The coach agreed. “Question is, who will score it?”

THE DESTROYER: In Chennai, when the

Australians managed to squeeze a tiny first innings lead, Sachin

Tendulkar walked up to coach Anshuman Gaekwad and said India

could have a sniff at victory if somebody scored a quickfire 80.

The coach agreed. “Question is, who will score it?”

Gaekwad asked Tendulkar, who had hit all of

four runs in the first essay. Sachin tapped his chest and said,

“Him Man!”—jargon he picked up last year in the

West Indies. “He promised 80 and went on to score 155. He is

stupendous. I don’t want to run out of adjectives describing

him,” says Gaekwad. Sachin puts it better: “This is a

game of situations, not averages.”

THE CREATOR: There were

titters in the Delhi hotel when the team for the 1996 England

tour was announced and Ganguly was in. “Tee-hee-hee,”

went the assembled journos mocking at his disastrous debut four

years earlier. Today, as the Bengal Tiger’s Bradmanesque

appetite for runs assumes man-eating proportions, Ganguly has the

same journos and commentators eating out of his hands.

“Saurav is a gem,” says the doyen of cricket writers

K.N. Prabhu. “With his sinuous grace that is part of the

Eastern mystique, he is in the mould of the great stroke players

like Ranji and Duleepsinhji.”

THE PRESERVER: On the

Caribbean tour last year, Sachin had trouble as most batsmen

coping with Curtly Ambrose. “I was finding it difficult to

read him,” Sachin told Amrit Mathur. “So I told Rahul

(Dravid) we will keep rotating the strike so that he doesn’t

get to bowl at any one batsman for too long.” Dravid,

India’s #1 all-track player, did so with aplomb. Little

wonder when the selectors dropped Rahul for the one-dayers, Kapil

Dev asked: “How can they? He’s the find of the

century.”

Ignore, for a moment, the stunning

second-innings collapse and defeat in Bangalore. And pan back,

instead, to Sachin’s breathtaking assaults in Chennai,

Calcutta and Bangalore; Saurav’s silken grace in England,

Toronto, Dhaka and Sharjah; and Rahul’s rocksolid

phlegmatism against all-comers in the last two years, and

you’ll begin to appreciate why the Awesome Threesome are

awash in adjectives. Why millions of worshippers are flocking for

a darshan of The Trinity.

Together with Navjot Sidhu and Mohammed

Azharuddin, they have totted up an astounding average of 61.83

runs per Test. Together, they have hit 17 centuries in the last

15 matches. No other No. 3 batsman in the solar system, including

Brian Lara, has an average higher than Rahul’s. At No. 4,

only Aravinda de Silva scores more runs per Test than Sachin. And

at No. 6, only Azhar Mehmood is marginally ahead of Saurav.

It’s Middle- order Terrorism.

Sure, Indian batsmen have justifiably earned

the tag of being tigers at home, running up obscene scores in

high-yield matches. But this is the first time in 20 years that a

top order has turned in such consistently good performances over

a 15-month period in Tests and one-dayers , at home and

away.Sachin has fared well in England Rahul has hit “In form

and focus, they’re the best just now. Their only competition

is Pakistan,” says Mike Coward, a columnist of The

Australian.

But, more than the numbers, it’s the

brutal manner in which the world’s least hyped side took

part the world’s most successful one, notwithstanding

Bangalore, is what has fans, fanatics and—let’s admit

it—critics and cynics yearning for more. “We have never

ever approached a series like this,” says veteran cricket

writer Raju Bharatan. Quips offspin legend Erapalli Prasanna:

“This is the most tenacious line-up I’ve seen.”

And probably the most balanced: the West (Sachin), South (Rahul)

and East (Saurav) holding up the hopes and aspirations of a

nation with the North (Sidhu) and Centre (Azhar) as axis.

But it’s Sachin who’s getting all the

plaudits just now, for it was he who made the difference between

the two sides in the series just gone by. For writing the first

draft of Azhar’s fairy tale with a double ton in

Mumbai’s encounter with the visitors which set the scene for

the butchery. And then for implementing it with a brutal alliance

of power, timing and precision in all three Tests.

Hitherto held back by a suspected lack of

meanness—determined rather than ruthless—Sachin did to

Shane Warne what he has been doing to Ranji bowlers for a decade.

Result: India’s wunderkind who’s been used to nothing

but applause has become a veritable trap for adjectives.

Sample some:

“Dennis Lillee said the other day that if

he had to bowl to Sachin he would bowl with a helmet on. He hits

the ball so hard. Lillee says Sachin’s the best player he

has seen in 10 years.”

ESPN commentator Harsha Bhogle.

“The more I see of him, the more confused

I’m getting as to which is his best knock.”

M.L. Jaisimha.

“There was Sunny. Then there was Kapil.

Sachin is beyond both. He’s something else.”

Ajay Jadeja.

“I always felt C.K. Nayudu was the best. I

now think Sachin has the honour of being the most outstanding

batsman of all time.”

Cricket historian Vasant Raiji.

The firangis, of course, are ecstatic:

“Sachin’s the best. I’ve had

this view since I saw him score that hundred in Sydney in 1992.

He’s the most composed batsmen I’ve ever seen.”

Mike Coward.

“Don Bradman says that Sachin’s the

one batsman who bats like he used to. It’s been a privilege

to watch his innings in Chennai and Bangalore.”

Ian Chappell.

“Tendulkar is the supreme right-hander on

the planet, a focused technician who offers a counterpoint to

Brian Lara’s more eye-catching destruction.”

Mike Selvey.

“Sometime back I had written a piece that

said Sachin is the master and Lara a genuis with his head high up

somewhere. That’s it.”

Peter Roebuck.

But it’s not what Sachin alone achieved in

the series in tandem with Sidhu and Azhar but what he can achieve

in tandem with Saurav and Rahul that has everyone cock-a-hoop.

“Sunny was saying the other day that these guys don’t

believe in weathering the bowling,” says Bhogle. It’s

bat and belt from the word go.Their arrival has all the classic

elements of modern-day India. When Sachin got a berth for

Pakistan, Tendulkar Senior had to sign the bcci contract because

Sachin was still a minor.Saurav had to inch his way back after he

was initially dismissed as an upstart riding the back of his

influential father Chandi. And Rahul, as always, had to grind his

way up.

But having converged, it seems there’s no

stopping the trio whose contrasting batting styles, too, offer a

range of possibilities that no emerging batting middle-order in

the world does. The naked devil-may -care aggression of Sachin,

the phlegmatic solidity of Rahul and the easy grace of Saurav.

“Batting numbers 3, 4, 5 and 6 are the players that really

count and no other team in the world has this kind of

depth,” says Prof Ratnakar Shetty of the Bombay Cricket

Association.

Ideally, says Bhogle, the top six should have a

batsman who can bowl: “With Saurav, India can develop that

option.” What’s more, adds Roger Binny, at No. 6,

“Ganguly can play off the second new ball as well”.

It’s a win-win all the way.

Saurav may have been oddly off-colour this

time, batting way down after the stars had blazed across the

greens, but make no mistake, the next big knock is always around

the corner for the sweetest timer of the red cherry. With the

applause growing for Sachin, there is an apprehension that the

other two might feel just a bit overawed, but Saurav doesn’t

bother about that: he just tries to do a better Saurav.“You

can’t try to do what somebody else is good at but you

aren’t.

That’s a recipe for failure,” says

the southpaw. Such levelheadeness comes easily to the three.

Dravid knows he lacks the power of Sachin and the touch of

Saurav, so he plays to his strengths, not weaknesses.

Sachin and Saurav

are already being compared to the best their cities have had to

offer. “The best-ever batsman from Bengal?” Raju

Bharatan asked in The Hindu and said Ganguly was even better than

Pankaj Roy although “there are still grey areas in his

onside play that he is in the process of shading white”.

Sachin and Saurav

are already being compared to the best their cities have had to

offer. “The best-ever batsman from Bengal?” Raju

Bharatan asked in The Hindu and said Ganguly was even better than

Pankaj Roy although “there are still grey areas in his

onside play that he is in the process of shading white”.

But Rahul’s hardboiled approach defies any

parallels with the skill and touch of his townsman: G.R.

Vishwanath. Where Vishy was the ultimate touch artiste, who

revelled when the chips were down and found it tough to find

motivation when India were sailing along, Dravid is all focus,

grinding his way in match after match, whether it’s 10 for 1

or a 100 for 1. Says Peter Roebuck: “The Indians regard him

as their own Steve Waugh, a fighter, resourceful and effective,

who looks like one of those stern and reclusive monks, to be

found in mountain retreats, whose wicket must be prised.”

Adds Indian coach Gaekwad: “Rahul’s more like Sunny.

Picks the right balls to hit. He’s also the best leaver of a

delivery.”

Rahul’s so far played uncomplainingly in

five batting positions, from No. 1 to 7, but as Harsha Bhogle

wrote in The Sunday Times of India, that’s only to be

expected of a man obsessed with the game: “He once walked up

to a twi producer with an unusual request. Not for a video

cassette but for a t-shirt. It had written on it, ‘Cricket

is Life. The rest is mere detail.’” A t-shirt Dravid

now sports in those Pepsi ads.

Dravid’s only known weakness—besides

his great ability to find very ingenious ways of getting

out—is his even greater inability to convert his 50s into

100s. In the last two years, he has been dismissed four times in

the 90s, and twice between 80 and 100. Sachin’s problem is

even curiouser: an inability to convert his 150s into 200s! Twice

in two years he has been dismissed after reaching 175 (Bangalore

and Trent Bridge).

Few doubt that this is the core of the Test team for the early

21st century. But the one-dayers are far from a cinch. Where

Sachin and Saurav have struck up a fruitful partnership at the

top, the selectors are finding it difficult to accommodate Rahul

in the middle in spite of his outstanding record.

Says Raju Bharatan: “I approximate

Dravid’s position with that of New Zealand’s Glen

Turner who too took a while to mesh with his side’s one-day

plans but did so very well after a stint on the English county

circuit. Dravid will no doubt do so as well but he needs to be

picked for the one-day side more often.”

Dravid may not have done his chances much good

for the triangular series and the Sharjah tour with his

pedestrian batting in the second innings in Bangalore but fans

will only point to his blitzkrieg against Alan Donald in South

Africa, when the chips were down, to rest their case.

“I would put Dravid ahead of Azhar any

day,” says veteran cricket writer Dicky Rutnagur.

“Dravid can score on all tracks. Azhar can’t. He

doesn’t even show an inclination to try. He just goes and

hits wildly. If it comes off, well and good. But so far it’s

clicked only four-five times: Adelaide, Lord’s, Cape Town,

Calcutta.”

But in quibbling over their respective

strengths and weaknesses, we may be missing the big picture for

the statistics. Point is, no other contemporary side has three

young batsmen of such variety, depth and calibre to bank on. The

West Indies has Brian Lara and Shivnarine Chanderpaul but Carl

Hooper is but an ageing warhorse. Australia has Greg Blewett and

Ricky Ponting, but their failure here should invite questions

about their competence against spin. Aravinda de Silva, Roshan

Mahanama, Arjuna Ranatunga and Hashan Tillekaratne are all in the

same age group.

Only Pakistan, as cricket writer Rajan Bala of

The Afternoon Despatch & Courier points out, has comparable

batting reserves as India’s: with Inzamam-ul-Haq and Azhar

Mahmood and Mohammed Wasim and Yousuff Youhana and whoever else

that country’s selectors may throw into the ring in the next

week/month/year. Says Bala: “Anwar, Sohail and Inzamam are

better players of pace. We only have Sachin and Rahul.”

Also, in spite of the horribly high average of the top six in the

past 15 months, India’s success rate remains a poor 50 per

cent, having just won only two of the 15 Tests under review.

Injuries to Javagal Srinath and Venkatesh Prasad, lack of form of

Anil Kumble and Rajesh Chauhan, ill luck (bad light, rain, stodgy

last-wicket stands) have accounted for a few losses. Yet, in a

game where statistics can often lie, they tell the horrible

truth: Remember this is the team that scored 66 in South Africa.

As former manager Madan Lal, who watched the

same boys fail to score 120 runs in Bridgetown, Barbados, points

out: “To qualify as a good batting side, you’ve to

score runs abroad as well. The Indians had a good time here

because the Australians had a weak bowling attack. Warne in India

is a 3 for 150 bowler, not 3 for 30 that he’s in

Australia.” Adds Rajan Bala: “I don’t see this

same team going to Australia and winning.”

Admittedly, cricket-frenzied Indians have seen so many hyped

“Teams

of the ’90s” go to pieces, so many defeats snatched

from the jaws of victory, so many hopes turn to despair that

it’s difficult to accept the gung-ho optimism that this side

exudes with equanimity.

“What decides and places a player in the

superlative bracket?” asked Sridhar Manyem of Dallas in The

Melbourne Age before the Australia series began. “It’s

how many victories he has helped his team achieve. Sachin might

have saved matches but in 10 years, there have been only 10

instances in which he has scored over 50 in an innings and India

has won a Test, and all but two of them have been in India. In

one-dayers too, it’s happened only on 33 occasions.”

With his latest exploits, Sachin may have

transgressed such transcontinental carping. But Saurav and Rahul

are aware of the hopes they carry on their young shoulders. At

man-of-the-match ceremonies, their refrain is painfully familiar:

“I’m glad with what I did with the bat, but I’d

have been happier if India had won.” In Dhaka, two months

ago, when Hrishikesh Kanitkar hit the 316th run, Ganguly placed

his 124 below Kanitkar’s four!

The real, sterner Tests lie ahead—that

too, abroad—but as Raju Bharatan points out, this series

marks a kind of coming together of an evolving side. Adds

Ratnakar Shetty: “I have seen the trio up close. Their

dedication and commitment shows there is a great future for

India. The appointment of a full-time trainer has also pleased

them because their abilities are being raised to the highest

potential.”Praise, like criticism, comes easily to us

Indians, eager to bury the humiliating defeats of the

not-so-distant past. “Remember, you were the guys who

dismissed The Class of ’96,” a player tells Outlook.

And as Azhar’s boys wallop the Aussies, we forget Sunil

Gavaskar’s lonely battles in the middle, and that

super-strong team he moulded in ’84-85: SMG, K. Srikkanth,

Dilip Vengsarkar, Mohinder Amarnath, Azharuddin, Ravi Shastri,

Sandeep Patil, Syed Kirmani, Kapil Dev.

“Gavaskar and Co had more mental

strength,” says Bishen Bedi. “For Gavaskar it was a

matter of proving to the world that Indians were as good as the

best. These guys don’t have to cross that road-block thanks

to him.” Adds Robin Singh: “If we just take the middle

order leaving out Gavaskar, I think Sachin, Azhar and Ganguly are

stronger than Vengsarkar, Vishy and Amarnath because they can

score at match-winning rates.”The sudden upbeat atmosphere

however is symptomatic of a nation that enjoys the game,

celebrates victories, denounces defeats, and then prepares for

the next match. Yet, as Mihir Bose reminds us in The History of

Indian Cricket: “A new cricket reign, glorious with promise

and gold is ‘always’ about to emerge, a new dawn

‘always’ seems ready to burst forth, only for the

blackest of clouds plunging the whole scene into utter, terrible

gloom.”

For the moment, though, it’s time to sip

the champagne. As bowlers around the world dread the thought of

facing Sachin after the hammering he gave Warne, they can draw a

small lesson from Detroit Piston, Dennis Rodman. Faced with a

similar situation against a rampaging Chicago Bull, Michael

Jordan, Rodman says they let him have his 40 points but shut the

others up.

THE DESTROYER: In Chennai, when the

Australians managed to squeeze a tiny first innings lead, Sachin

Tendulkar walked up to coach Anshuman Gaekwad and said India

could have a sniff at victory if somebody scored a quickfire 80.

The coach agreed. “Question is, who will score it?”

THE DESTROYER: In Chennai, when the

Australians managed to squeeze a tiny first innings lead, Sachin

Tendulkar walked up to coach Anshuman Gaekwad and said India

could have a sniff at victory if somebody scored a quickfire 80.

The coach agreed. “Question is, who will score it?”  Sachin and Saurav

are already being compared to the best their cities have had to

offer. “The best-ever batsman from Bengal?” Raju

Bharatan asked in The Hindu and said Ganguly was even better than

Pankaj Roy although “there are still grey areas in his

onside play that he is in the process of shading white”.

Sachin and Saurav

are already being compared to the best their cities have had to

offer. “The best-ever batsman from Bengal?” Raju

Bharatan asked in The Hindu and said Ganguly was even better than

Pankaj Roy although “there are still grey areas in his

onside play that he is in the process of shading white”.